BBC Verify

BBC

BBCPresident Donald Trump has fired the head of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (LBS) after the department revised down recent job numbers by more than 250,000.

He says the figures were “rigged” to make his administration “look bad”.

Although the latest revisions were bigger than usual, it is normal for the initial monthly number to be changed and it has happened routinely under both Democratic and Republican presidents.

How are the job figures collected?

The BLS head – known as the commissioner – plays no role in collecting the data or putting the numbers together, only stepping in to review the final press release before its published, according to former commissioners.

“My reaction was, ‘That couldn’t happen,'” says Katharine Abraham, who served as BLS commissioner from 1993 to 2001, about Trump’s claims that the numbers had been rigged.

“The commissioner doesn’t have control over what the numbers are,” she adds.

The jobs report from the BLS is based on two surveys – one that collects data from about 60,000 households and another from 121,000 public and private sector employers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe estimates of job gains come from the survey of employers, often referred to as the establishment survey. It tends to be considered more reliable than the household survey because of its large sample size.

A majority of the responses come from large firms, typically enrolled in a programme that automatically submits their employment information. BLS staff also run web surveys and telephone interviews.

“The initial estimates of payroll employment are a preliminary look at what occurred in each month,” the BLS told BBC Verify.

“It is the quick but lower-resolution snapshot of what went on in the job market for a particular month. Because the revised estimates are based on more complete data, they create a higher resolution picture – and occasionally the revised data produce a different picture,” it added.

The bureau updates the figures in the two months following the initial monthly estimate, as more responses come in. It also recalculates the numbers annually to incorporate data from unemployment insurance tax records.

“There are all of these career people who also have the data and if the commissioner were to try to change the numbers they would all know and it would get out,” Prof Abraham says.

How unusual are the latest revisions?

The figures for May and June have been revised down by 125,000 and 133,000 respectively.

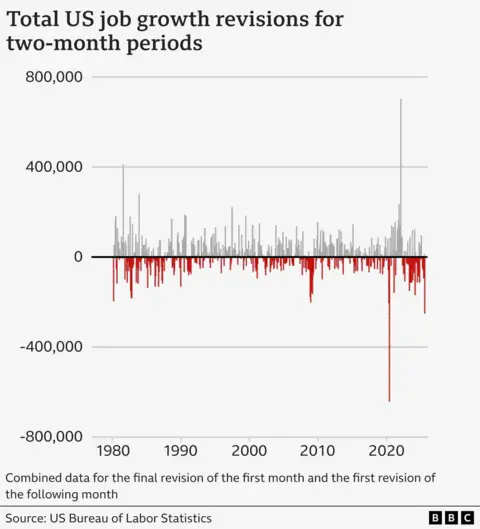

The 258,000 combined reduction total for the two month period represents the biggest change since records began, aside from the months in 2020 following the outbreak of the Covid pandemic.

However, there are adjustments every month and large changes are not unprecedented.

In this case, many analysts were already expecting revisions to the June figures, which had showed an unusual rise in school employment during a month when most schools were about to close for the summer.

Later responses also disproportionately reflect smaller firms, which are more vulnerable to changes in the economy such as tariffs, analysts note.

The May figure was adjusted down largely in response to the June revision and is consistent with other data showing a slowdown.

In records going back to 1979, the average monthly change to the jobs figures (either up or down) is 57,000, according to the BLS.

But revisions tend to get bigger during times of economic turmoil.

Aside from the most recent numbers and the 2020 Covid period, there have been eight other occasions since 2000 when the BLS revised down monthly job numbers by more than 100,000 – with most of these coming around the 2008 financial crisis.

For instance, there was a 143,000 reduction to the January 2009 figure when President Barack Obama was in office.

The BLS also said job gains for the entire year in 2009 were 902,000 lower than it first estimated – the largest full-year revision on record.

The jobs created in 2024 under President Joe Biden were revised down by 598,000, though that was a smaller change than the more than 800,000 initially estimated – an update which also caused political fallout.

Prof Abraham says updates are part of the process and she was not surprised to see such large revisions for May and June, given increased difficulty of collecting responses and lack of investment in new methods – and the wider slowdown in the economy, driven in part by new tariffs.

“It’s always difficult when you’re at a point where things may be changing and then you add to that the fact that staffing has been constrained and the agencies haven’t had the resources to invest in following up with respondents the way they might have in the past,” she says.

Have there been problems with the data in the past?

Response rates have dropped significantly over the last decade, accelerating after the pandemic, raising concerns about the reliability of the data.

For example, the response rate for the establishment survey was less than 43% in March, compared with more than 60% a decade earlier.

Other countries, including Canada, Sweden and the UK, have been wrestling with similar falls. Response rates to the labour force survey have fallen to roughly 20% in the UK.

In the US, the drop-off has sparked some efforts to explore new methods of data collection, including web-based surveys.

But the significance of the problem remains a matter of debate.

A review by researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco in March of this year, found that revisions in recent years were mostly in line with pre-pandemic patterns, which it said should be reassuring to those worried about reliability.

Source link

Unews World

Unews World